The AI Design Playbook for Startups

Four frameworks every startup needs before embedding AI into their product — because AI is rewriting the rules of product strategy, but the teams breaking out aren’t the ones chasing the newest model

This week, we’re going deeper into a question every founder is wrestling with right now: how do you design AI into your product in a way that creates real competitive advantage — not gimmicks but durable differentiation?

AI is rewriting the rules of product strategy, but the teams breaking out aren’t the ones chasing the newest model or stacking on features. They’re the ones getting the earliest design choices right: when to use AI, how users should interact with it, what to make transparent, and where to draw the line between autonomy and control. Those decisions don’t just shape UX — they shape trust, adoption, and long-term defensibility.

In today’s edition by Rupa Chaturvedi, we share The AI Design Playbook for Startups, a set of field-tested frameworks drawn from building and advising AI products at Amazon and across dozens of early-stage teams. If you’re building in AI — this is the guide you want before your product decisions harden into architecture.

This week’s guest post:

Rupa Chaturvedi is the founder of the Human Centered AI Institute, where she leads corporate training and consulting programs in AI product design. She also teaches a top-rated course on Maven — Master UX Design for AI. NEW ECONOMIES readers can enjoy an exclusive 15% code.

An ex-Amazon/Google/Uber design leader with 15+ years of experience shaping AR, AI, ML, and computer vision–driven consumer technologies, she has published 18+ patents and taught UX Design for AI at Stanford. Her work centers on humanizing technology and empowering professionals to design intelligent systems that inspire trust and impact.

The AI Design Playbook for Startups

You’re competing against larger companies with more resources and incumbents with established user bases. You need to make product decisions that create real differentiation, not just add AI because everyone else is. The startups gaining ground made deliberate choices about how AI fits into their product.

The pattern I see working across teams I’ve worked with and advised: they get foundational design decisions right early, before those choices get embedded in architecture and user expectations.

These aren’t the only factors in building successful AI products. Distribution matters. Timing matters. Your specific market and user needs matter more than any framework. But when you’re making foundational design choices, having clarity on a few key dimensions accelerates your team and reduces costly build-then-abandon cycles.

Here are four frameworks that I’ve developed from working with teams, frameworks that help them make those decisions deliberately rather than defaulting to what’s technically possible or mimicking what worked for someone else’s product.

When to Use AI (And When Not To)

Early in my time at Amazon, I was part of the team building AI-powered shopping features for Alexa. The vision was compelling: you could access advanced AI in a way that felt like talking to another human, shop conversationally, and have products delivered to your doorstep. We built the full stack for voice-based browsing, recommendations, and checkout, assuming this natural progression would resonate with users since they already trusted Alexa for so many daily tasks.

But voice shopping never gained the traction we expected. The technology worked perfectly from an engineering standpoint, but we had missed something fundamental about how people make purchasing decisions. When you’re spending money on products, you need to see options side by side, read reviews, compare prices, and check specifications. Voice interaction made all of these essential behaviors harder rather than easier. We had built around what the AI could do rather than starting with what users actually needed to accomplish.

The contrast became clear when I later worked on Amazon’s AR shopping experience. AR View started from a different premise: what if we could solve the specific friction points in furniture shopping? The problem was real and costly. Buying furniture means waiting for delivery, assembling it, assessing whether it fits your space and aesthetic, and then potentially going through the painful process of disassembly and return if it doesn’t work. Most people can only realistically try one or two options before giving up. AR View changed this by letting users virtually place furniture in their actual living space using their phone’s camera. You could try thirty different couches in ten minutes and see exactly how each one would look in your room. The value showed up immediately in time saved, confidence gained, and returns avoided.

The Real Question Before Building AI

These two experiences taught me that the critical question isn’t whether we can build something with AI. It’s whether the AI creates more value than the solutions users already have. When someone adopts your AI feature, they’re making a trade. They’re giving up control and predictability in exchange for whatever benefit you’re offering. That benefit needs to be concrete and measurable: time saved, money saved, fewer steps to accomplish their goal, or an experience that’s so much better they’re willing to change how they work. If you can’t articulate that value in specific terms, your users won’t understand it either, and they won’t make the trade and adopt your solution.

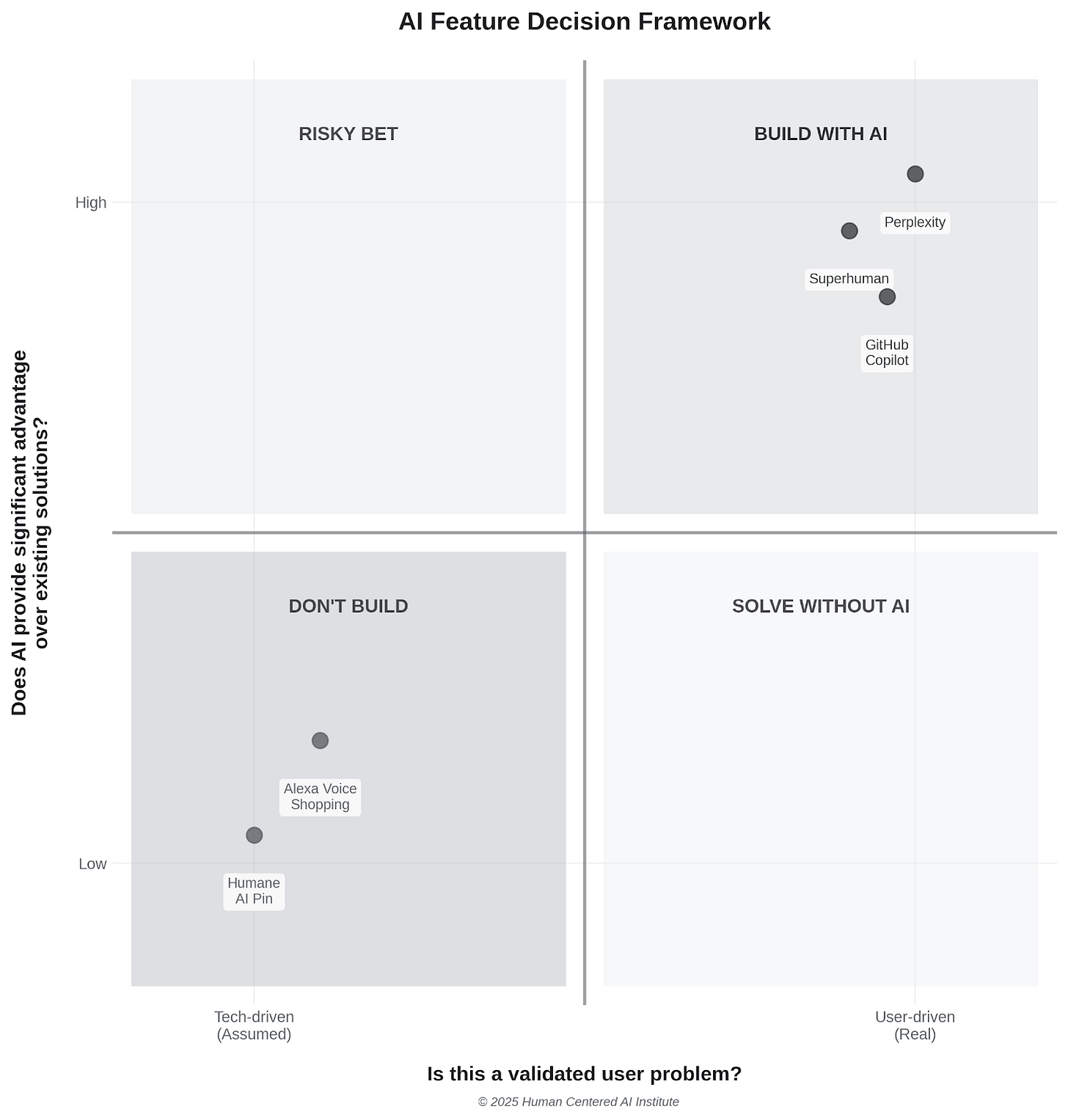

Mapping AI Opportunities: Problem Fit vs Value Delivered

Before investing in AI features, you may need a way to evaluate whether you’re solving a real problem or just building impressive technology. Here’s a framework you can use to assess opportunities across two dimensions: whether you’re solving a genuine user problem, and whether users are actually adopting it.

The question is whether you’re building because the technology enables it, or because users have a specific problem you’re solving. The other question is whether you can measure adoption that proves the value.

Products in the upper right quadrant demonstrate strong adoption. Perplexity gained traction with users who previously relied on Google because getting a complete answer used to mean running multiple searches and piecing together information from different sources. Superhuman has professionals paying $30/month to migrate from free email clients because the AI helps them process hundreds of emails faster. GitHub Copilot sees developers accepting a significant portion of its code suggestions because it reduces time spent writing repetitive code patterns.

The lower left quadrant shows where adoption didn’t materialize. Alexa’s voice shopping feature saw users try it once or twice before returning to visual browsing. The Humane AI Pin got limited traction because it didn’t offer advantages over existing smartphones. In both cases, the technology worked as designed, but users stayed with their existing solutions because those already met their needs effectively.

If you’re explaining your AI feature primarily through what the technology can do rather than what user problem it solves, that signals you’re on the left side of the framework. If you can’t quantify the value or articulate why users would trade control for your AI’s benefits, you’re likely in the lower half.

When to Use Chat (And When Not To)

A team I worked with built an AI-powered analytics tool for e-commerce businesses with a conversational interface. Users could ask questions about sales data, customer behavior, and inventory trends. The demos were impressive, but adoption stayed low. The issue became clear through user research: merchants weren’t exploring open-ended questions the way the team expected. They were checking the same metrics repeatedly—yesterday’s sales, top products, current inventory levels. Typing conversational queries for routine checks was slower than scanning a dashboard. The chat interface added friction to tasks that needed speed.

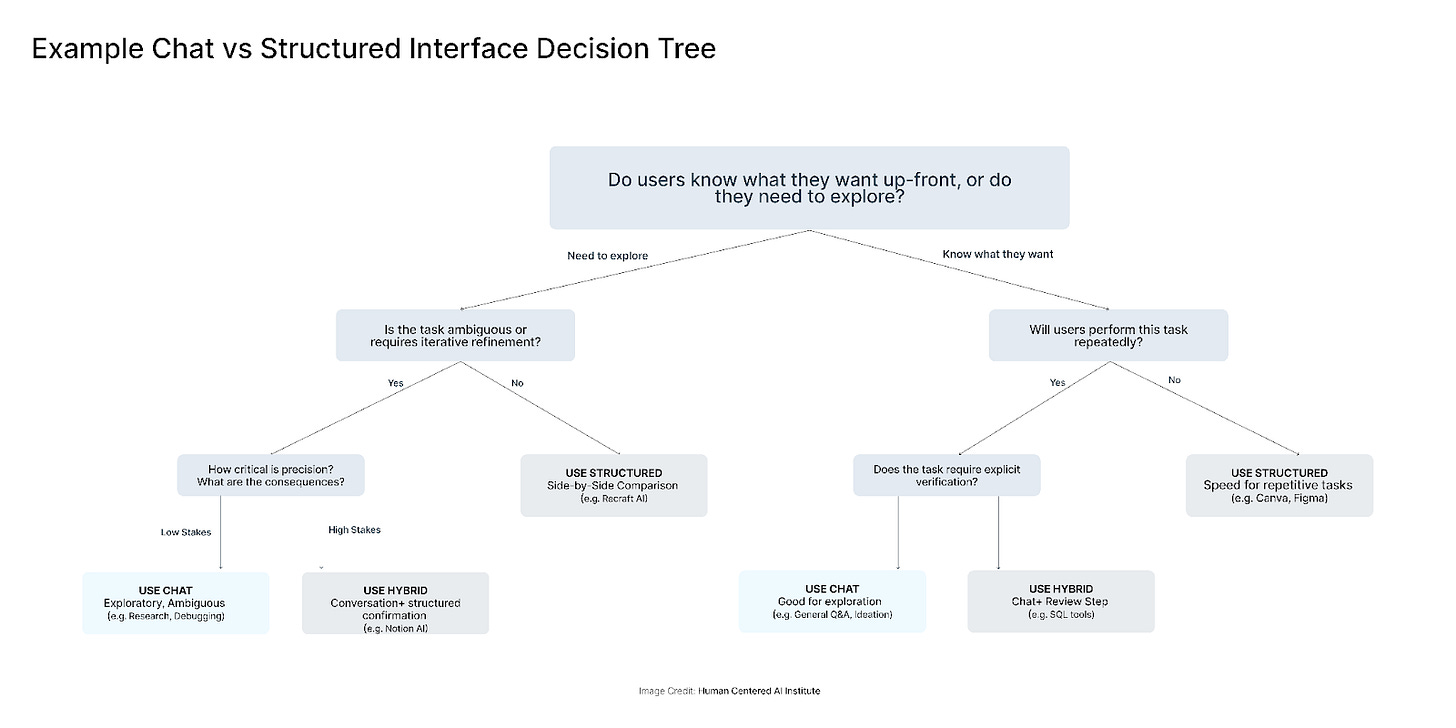

ChatGPT’s success made conversational interfaces the default template, often without examining whether conversation actually serves the use case. But chat works brilliantly for some problems and creates unnecessary overhead for others. Before choosing an interaction pattern, you need a way to evaluate whether conversation matches how users actually work.

The decision comes down to a few questions about your core use cases:

First, do users know what they want upfront, or do they need to explore possibilities? Research works conversationally because you start broad (”How does CRISPR work?”) and narrow based on what you learn (”What are the ethical concerns?”). The dialogue matches exploratory thinking. Debugging code follows a similar pattern—context narrows toward a solution through back-and-forth clarification.

But if users perform the same task repeatedly, conversation slows them down. Canva uses templates and parameters rather than chat because design tasks are often routine and inputs are predictable. The difference isn’t about AI capability—it’s about matching the interaction to the job.

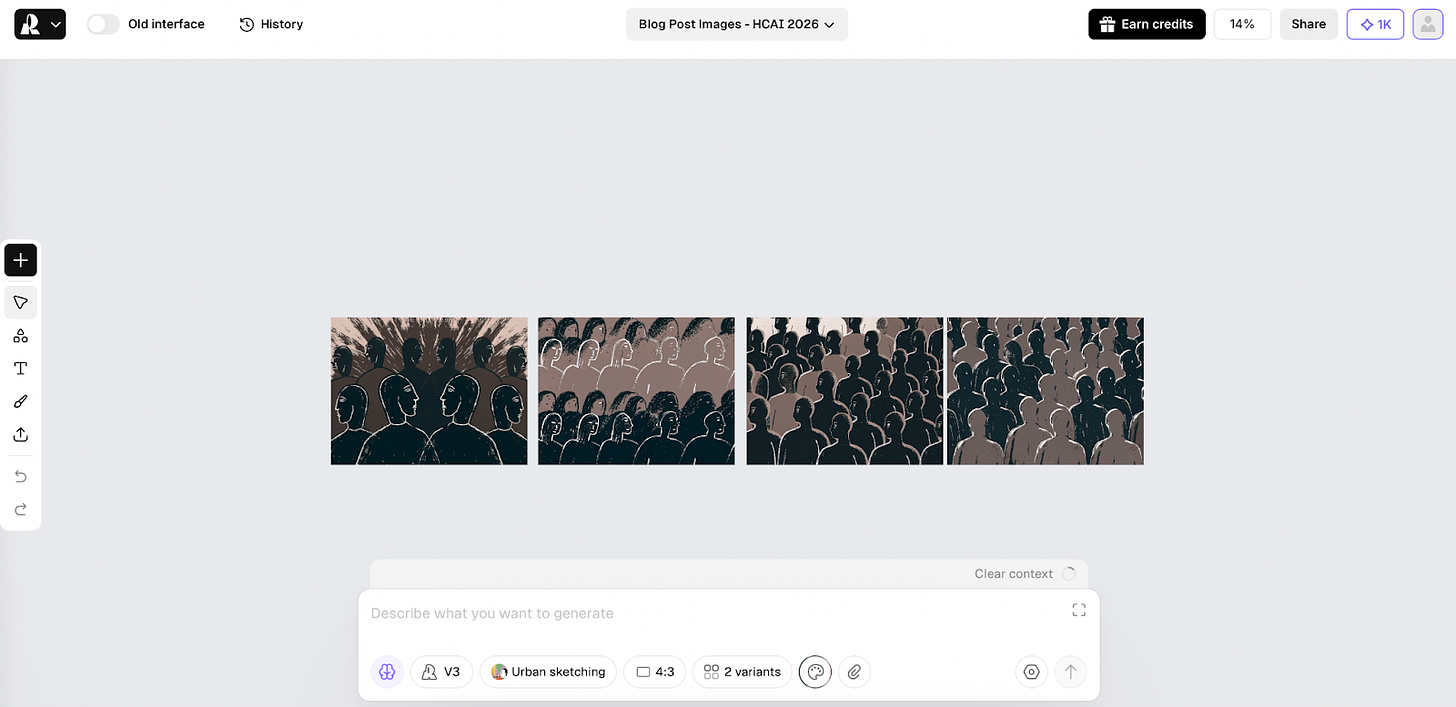

The second question is whether users need to compare options side by side. Generative AI tools like Recraft.ai show multiple image variations simultaneously so users can see differences at a glance and iterate on specific options. Describing variations one at a time conversationally would slow the creative process significantly. Sequential presentation works for research where each answer builds on the last. It fails for tasks that require simultaneous comparison.

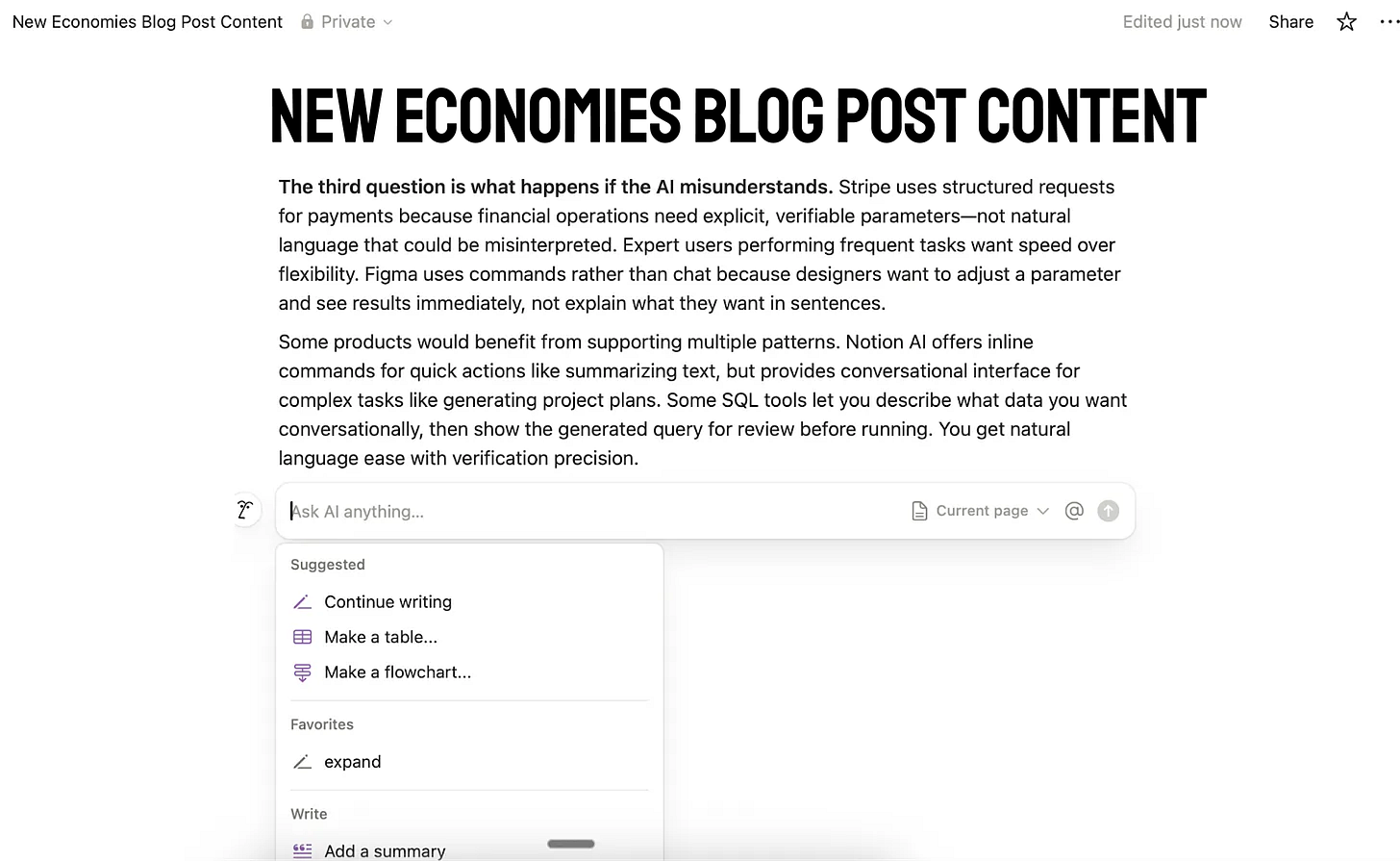

The third question is what happens if the AI misunderstands. Stripe uses structured requests for payments because financial operations need explicit, verifiable parameters—not natural language that could be misinterpreted. Expert users performing frequent tasks want speed over flexibility. Figma uses commands rather than chat because designers want to adjust a parameter and see results immediately, not explain what they want in sentences.

Some products would benefit from supporting multiple patterns. Notion AI offers inline commands for quick actions like summarizing text, but provides conversational interface for complex tasks like generating project plans. Some SQL tools let you describe what data you want conversationally, then show the generated query for review before running. You get natural language ease with verification precision.

The choice depends on how your users actually work. Chat serves exploratory, ambiguous needs where dialogue helps clarify intent. Structured interfaces serve routine tasks, comparison needs, and situations where precision matters. The question isn’t whether chat is good or bad - it’s whether conversation fits your specific users doing your specific tasks.

Designing Transparency to earn Trust

Last year I advised a startup building a hiring coach that would help recruiters screen candidates and make better decisions. They piloted it with ten recruiters and hiring managers in the organization. The system was smart—it could analyze resumes, assess fit, and suggest who to interview. But adoption stalled almost immediately.

The problem became clear in the first week. The tool would tell recruiters “This candidate is a strong match” or “Consider interviewing this person next,” but gave no explanation of why. Recruiters couldn’t verify the reasoning. When a hiring manager asked “Why are we interviewing this candidate?” the recruiter had no answer beyond “The system recommended them.” That wasn’t enough to justify their time or defend their choices.

The team added a simple change: show which qualifications the system weighted most and how each candidate scored on key criteria. Suddenly recruiters started using it. The underlying recommendations didn’t change, but now recruiters could see the logic, verify it matched their own judgment, and explain decisions to others.

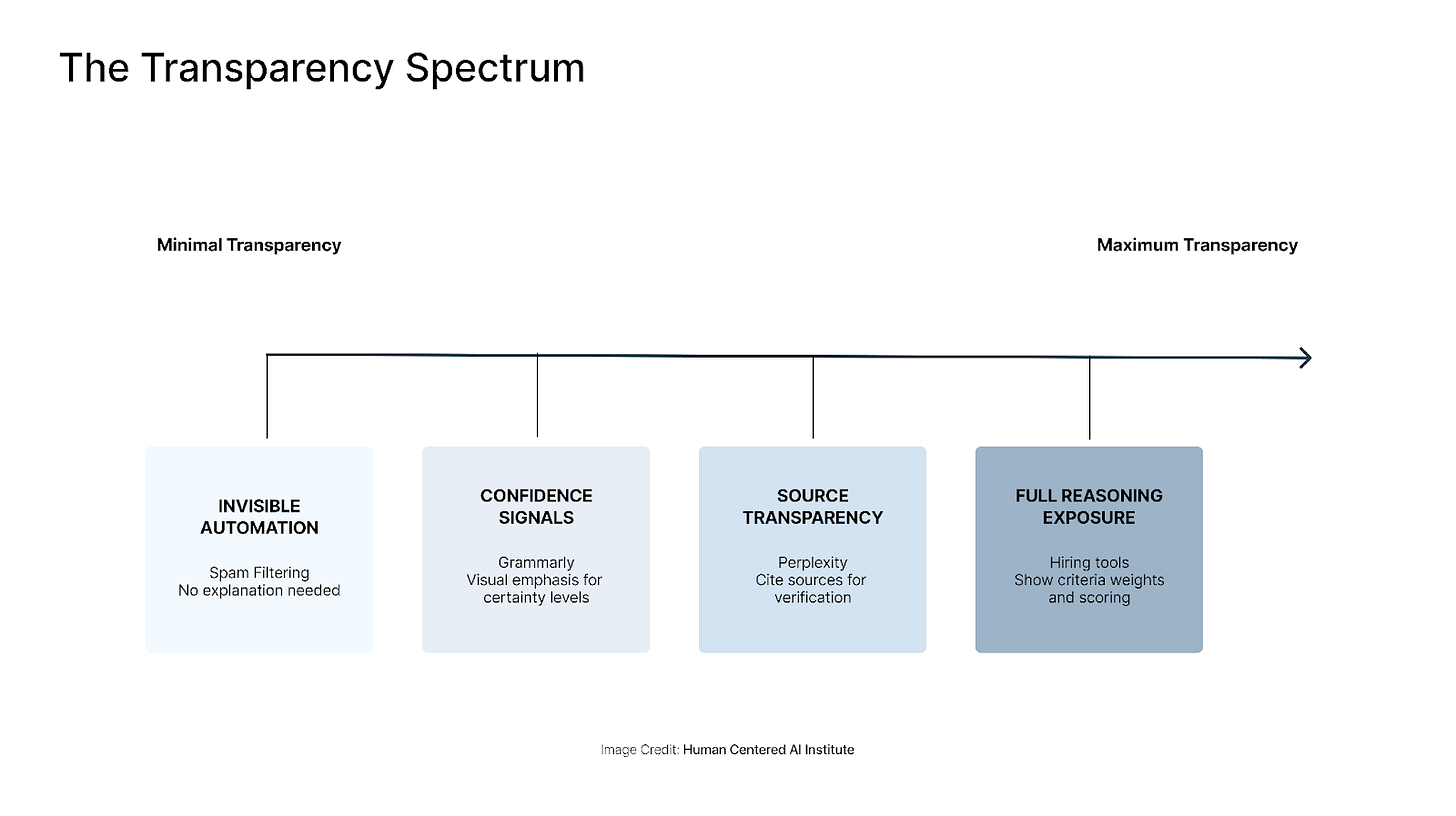

Users won’t trust what they can’t verify. But transparency has costs—too much explanation creates complexity and clutter. The challenge is figuring out what users actually need to see.

Transparency exists on a spectrum. Spam filtering works invisibly—users don’t need or want to understand how messages get categorized. Medical diagnosis tools must show reasoning chains, data sources, and confidence levels because lives depend on verification. Most AI products fall somewhere between.

The starting point is confidence signals. Grammarly uses strong visual emphasis for critical grammar errors and lighter styling for suggestions that require judgment. Color coding, solid versus dotted lines, or language like “based on limited data” work when applied consistently. Users learn to read the signals.

When stakes increase, users need to see what information the system used. Perplexity cites sources so users can verify claims. Financial trading algorithms show the logic behind recommendations because users stake money on trusting them. Any time users need to defend or explain a decision to others, they need access to the underlying reasoning.

The practical question is where your use case falls. Think about what could go wrong if users trust your system blindly, then design the minimum transparency needed to prevent that risk. If mistakes damage professional reputation, users need enough detail to verify before acting. If errors are easily reversible and low-stakes, minimal transparency may be sufficient.

Balancing Delegation and Control

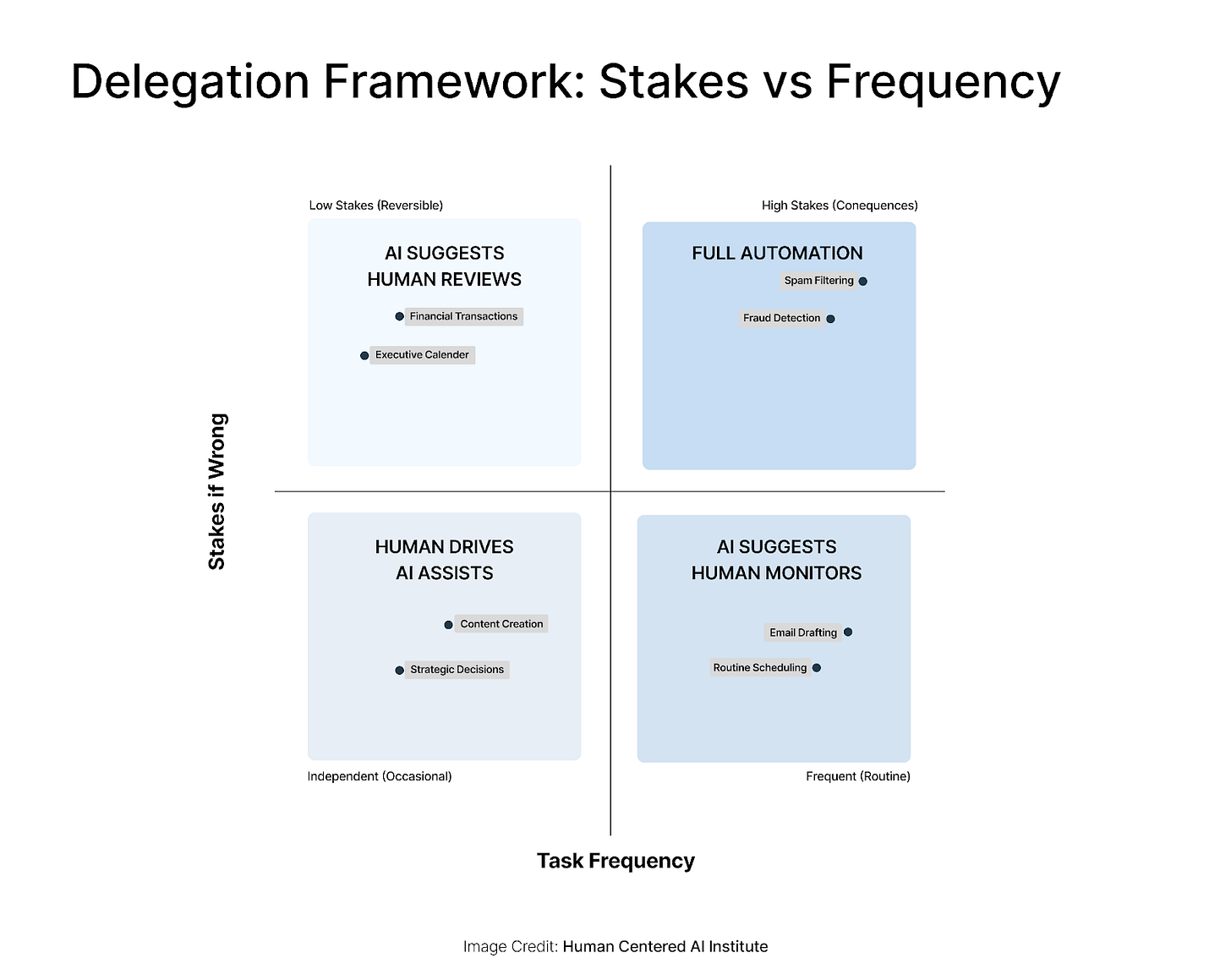

I’ve trained over 1500 professionals at top companies on building AI products, and I’ve reviewed hundreds of their agentic workflow projects. The question that comes up consistently, across every team: how do we make the right design decisions when it comes to delegation? How much should we delegate? When should we delegate? What triggers should loop a human in? When do humans need to review versus just monitor? How much oversight versus autonomy?

These aren’t abstract design questions. Teams are building systems right now where these decisions directly affect whether users adopt the product or abandon it. Get the balance wrong in either direction and you lose users—either because the AI doesn’t save them enough time, or because it acts in ways they can’t predict or control.

The pattern I see across failed projects is teams defaulting to either extreme. Some automate everything possible because that feels like the future of AI. Others keep humans in every decision because they’re worried about errors. Neither approach works. The right level of delegation depends on two factors: how often the task happens, and what’s at stake if it goes wrong.

Think about email. Spam filtering is low-stakes and happens constantly—hundreds of messages daily. Users want full automation. They don’t want to approve every spam decision. The occasional false positive is annoying but easily corrected. Gmail automates this completely and users trust it because the cost of being wrong is low.

But sending an email on your behalf is different. Even though it’s also frequent, the stakes are higher. A poorly worded message can damage professional relationships. Notion AI and other writing assistants generate drafts but don’t send them. Users review, edit, and decide when to hit send. The AI saves time on drafting, but humans retain control over the final output.

Financial transactions show the high-stakes pattern clearly. Fraud detection needs to be automated because it happens constantly and speed matters. But the system flags suspicious transactions rather than blocking accounts automatically. A human reviews before taking action that could lock someone out of their money. The frequency demands automation, but the stakes require human judgment.

Calendar scheduling falls in an interesting middle ground. Scheduling a routine team sync is low-stakes and frequent—full automation makes sense. But scheduling with an executive or external client has higher stakes. Users want to review before the AI sends invites. Tools like Calendly handle this by letting users set different rules for different meeting types.

The framework is straightforward. Map your specific use case: How often does this task happen? What goes wrong if the AI makes a mistake? High frequency and low stakes suggest full automation. High stakes regardless of frequency means humans review before action. Low frequency regardless of stakes often means AI assists but humans drive.

The trigger design matters as much as the delegation level. When does the system pause and ask for human input? Stripe flags transactions over certain amounts or from new locations. The hiring coach surfaced candidates but let recruiters decide who to interview. GitHub Copilot suggests code but requires developers to accept it. The pattern is consistent: automate the routine, surface the exceptions.

Think about your specific use case. What happens if your AI gets it wrong? Can users easily undo the action, or is damage permanent? How often will this happen—dozens of times daily or once a month? The answers tell you where you fall on the matrix and what level of delegation makes sense.

Conclusion

The products seeing real adoption—Perplexity gaining traction against Google, Superhuman converting users to paid plans, GitHub Copilot reaching high acceptance rates—share something beyond technical capability. They made deliberate choices about when to use AI, how users interact with it, what users can see, and how much autonomy the system has. Those decisions compound into products users trust enough to change their workflows.

These frameworks aren’t exhaustive, but they’re foundational. They give cross-functional teams a shared language for decisions that typically fragment across product, design, and engineering. When product wants full automation, design wants user control, and engineering optimizes for what’s technically feasible, these frameworks create alignment around what actually serves users. That alignment accelerates shipping and reduces the expensive cycles of building features users don’t adopt.

Your users have solutions that work. The bar for adoption is high. But when you’re deliberate about these core decisions, you build something users choose not because it’s technically impressive, but because it’s genuinely better in ways they can trust and control.

If you enjoyed this edition, help sustain our work by clicking ❤️ and 🔄 at the top of this post.

Join Rupa’s course: Master UX Design for AI

Learn to design AI products that are intuitive and valuable. Build your AI project portfolio, get certified as an expert in UX for AI. NEW ECONOMIES readers can enjoy an exclusive 15% code.

Great article, Rupa!

I love how you framed the key decisions and it matches what I've seen in my work.

Brilliant, brilliant piece!